Huashan Day 2: Descent back to Madness

Sunday, October 3rd, 2010 in: News

The nearly vertical section of stairs we had to climb to get to the East peak was completely swarmed with people. The queue stretched for a hundred meters, which of course bulged into a massive amorphous blob of humanity, trying to funnel its way down the step ladder as people pushed in and jockeyed to get down first. It’s amazing that this kind of behavior is tolerated; both in the US and UK, these queue jumpers would get soundly scolded and sent to the back of the line, but here it’s such common behavior, it seems that you’re just foolish not to cut in line here. You have to push to get ahead.

httpvh://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dt46FVz-1Dc

We refused to bend to the local custom, partially out of principle, and also because we saw that these queue jumpers, circumventing the established trail and crowding around the top of the ladders were creating a really dangerous environment. To my amazement, the few people who did shout out in protest weren’t scolding the queue jumpers, but rather the people at the bottom of the ladder who were trying to push their way up to get to the top. Both were a menace to the crowd, but it was the unseen offenders at the base of the cliff who were worthy of scorn. Dan and I found ourselves quietly cursing our manners and actually hoping someone would fall just to illustrate the threat all this queue jumping posed to everyone in the crowd–fortunately there was no such luck. It took over an hour to get to the bottom of the ladder. Determined to not let it ruin our trip, we soldiered on towards the South peak, and the 长空栈道, the plank walkway nailed into a sheer cliff 1,500 meters above the deck. Images of this walkway were the biggest initial motivation to come to this mountain, and I was determined not to let a bunch of poorly behaved people interrupt my plans.

We refused to bend to the local custom, partially out of principle, and also because we saw that these queue jumpers, circumventing the established trail and crowding around the top of the ladders were creating a really dangerous environment. To my amazement, the few people who did shout out in protest weren’t scolding the queue jumpers, but rather the people at the bottom of the ladder who were trying to push their way up to get to the top. Both were a menace to the crowd, but it was the unseen offenders at the base of the cliff who were worthy of scorn. Dan and I found ourselves quietly cursing our manners and actually hoping someone would fall just to illustrate the threat all this queue jumping posed to everyone in the crowd–fortunately there was no such luck. It took over an hour to get to the bottom of the ladder. Determined to not let it ruin our trip, we soldiered on towards the South peak, and the 长空栈道, the plank walkway nailed into a sheer cliff 1,500 meters above the deck. Images of this walkway were the biggest initial motivation to come to this mountain, and I was determined not to let a bunch of poorly behaved people interrupt my plans.

A temple by the walkway was swamped with yet more tourists. Dan lay down for a moment and I went to use the bathroom, which turned out to be just a hole in the floor so people’s waste would just slide down the side of the mountain. I told Dan about this. “Of course they’d do that, there’s no one living on THIS side of the mountain yet.”

A temple by the walkway was swamped with yet more tourists. Dan lay down for a moment and I went to use the bathroom, which turned out to be just a hole in the floor so people’s waste would just slide down the side of the mountain. I told Dan about this. “Of course they’d do that, there’s no one living on THIS side of the mountain yet.”

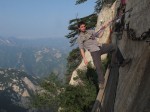

The walkway was pretty much as advertised, but you had to spend an extra 30 yuan to walk the boards, and they hooked us up to a chest harness with two anchors to ensure that we always had at least one clip affixed to the safety lines running above the chain handrails. Unfortunately, the safety equipment robbed us of any sense of danger, and we were able to maneuver effortless around the Chinese tourists clinging to the rails. Their anxiousness was amusing, considering they consistently misused the equipment, missing the point of redundancy by unclipping both carabiners at once. There was only one walkway, so we had to go around people on their way back. Whenever they went around me, they would practically hug me as they passed to give themselves something to hang onto. The walkway wasn’t very long, leading up to natural platform with a squat cypress tree reaching out over the edge of the cliff. The tree was draped in a blanket of red flags, evidence of foolhardiness.

The walkway was pretty much as advertised, but you had to spend an extra 30 yuan to walk the boards, and they hooked us up to a chest harness with two anchors to ensure that we always had at least one clip affixed to the safety lines running above the chain handrails. Unfortunately, the safety equipment robbed us of any sense of danger, and we were able to maneuver effortless around the Chinese tourists clinging to the rails. Their anxiousness was amusing, considering they consistently misused the equipment, missing the point of redundancy by unclipping both carabiners at once. There was only one walkway, so we had to go around people on their way back. Whenever they went around me, they would practically hug me as they passed to give themselves something to hang onto. The walkway wasn’t very long, leading up to natural platform with a squat cypress tree reaching out over the edge of the cliff. The tree was draped in a blanket of red flags, evidence of foolhardiness.

We turned back to hit the South peak, the highest point in the mountain range, squeezing around the Chinese tourists clinging to the side of the cliff in desperation. A couple of Canadian guys we’d met on the way up passed us on the planks. They shared a similar experience huddled on the South peak, suffering through the raucous behavior of their Chinese counterparts, but seemed much better rested than us. I suppose the bulk of the crowd was with us on the East peak for the best view of the sunrise. We wished them godspeed and continued up towards the South peak, past natural caves that had reportedly been used by Taoist hermits for thousands of years. Either there weren’t any hermits left or they’d moved elsewhere to avoid the million or so people that trudge up and down the mountain every year. Taoism is an interesting religion, as its influence is still very visible in Chinese practices and customs (Chinese medicine seems very strongly influenced by Taoism), but it’s not really “practiced,” but Taoist relics, like Buddhist ones, are merely preserved to show respect. Earnest practice of any particular religion isn’t forbidden, but I have a feeling that the government is pretty nervous about the existence of a “higher power” than itself. Trouble seems to follow devout followers of a faith for a multitude of reasons, just look at the Buddhist and Muslim minorities, or the Falun Gong. The whole issue of religion in China seems very warped. The Taoists are the only ones who had the foresight to dissolve into the cultural fabric, dyeing their influence into the Chinese national character but washing itself of the religious fluff that gets its cohorts in trouble.

We finally got up to the South peak and took in the view. Despite the crowds, it’s hard not to recommend this hike; the landscape is just so majestic, it’s still worth putting up with the throng of gawking Chinese tourists. We made our way to the West peak, the last destination before our descent back down to ground level. Although it wasn’t nearly as high as the South peak, it was the only one visible for the first half of the hike, and it’s sharp profile was both inspiring and frightening. I wondered if anyone tried base jumping from these cliffs, it totally would have been an improvement over the 2 hour hike down that left our shins screaming at us. Our climb was slowed by the flow of people trying to ascend the mountain, but we still made it down in record time.

Leave a Reply